“The development of full artificial intelligence could spell the end of the human race….It would take off on its own, and re-design itself at an ever increasing rate. Humans, who are limited by slow biological evolution, couldn’t compete, and would be superseded.”

— Stephen Hawking

Editor’s note: Because this issue is so crucial to our lives, I’ve broken the original post down into these six topics—each in their own post to allow for easier reading.

This is a huge topic. That’s why the original post was comprised of more than 7,000 and why I have broken it out into five separate posts. Even so, it didn’t cover nearly every aspect of the importance of AI to our future. My hope is to motivate readers to think about this, learn more, and have many conversations with their families and friends.

I’ve broken the original post down into these six topics—each in their own post. Feel free to jump around.

- An introduction to the opportunities and threats we face as we near the realization of human-level artificial intelligence

- What do we mean by intelligence, artificial or otherwise?

- The how, when, and what of AI

- AI and the bright future ahead

- AI and the bleak, darkness that could befall us (this post)

- What should we be doing about AI anyway?

These new intelligences could also bring with them some pretty terrible things, for us. First, though, there are likely some consequences that will arrive prior to the AGI (Artificial General Intelligence) or ASI (Artificial Super Intelligence). We’re already seeing some of these: automated weapons systems, increased surveillance activities, and loss of privacy and anonymity. These are things that humans are directing machine learning, artificial intelligence, and robotics to do.

The motivations for these things are pretty clear — safety and security, strategic advantage, economic gains — because they are the same sort of things that have been motivating humans for millennia. While we may not agree with the tactics, we recognize why someone may use them.

This won’t be the case with superintelligentand AI systems. There won’t likely be malice when we are eliminated. It just may be the most logical or efficient course of action. Referring back to the ants; we don’t have malice when we wipe out a colony of ants to build a new highway. We simply don’t think of the consequences for the ants because they don’t warrant that type of concern. Which brings us to the largest fear that those involved in AI research have: that we are bringing about our extinction.

Can’t we just pull the plug? Don’t they just do what we program them to do? They wouldn’t want to hurt us, would they? Who would be in charge of an ASI? All these questions point out the big problem with developing AGI and, by proxy, ASI: we simply don’t know what life will be like after ASI arrives. We’re creating something that could change nearly everything but we really do not know in what ways.

There are four main scenarios where things could go very wrong for us:

- A self-improving, autonomous weapons system “breaks out”.

- Various groups will race to develop the first ASI and use it to gain advantage and control.

- An ASI itself will turn malicious and seek to destroy us.

- We don’t align the goals of the ASI with our own.

Now let’s look at each of these in turn and determine just which we should concern ourselves with the most.

1. A self-improving, autonomous weapons system “breaks out”.

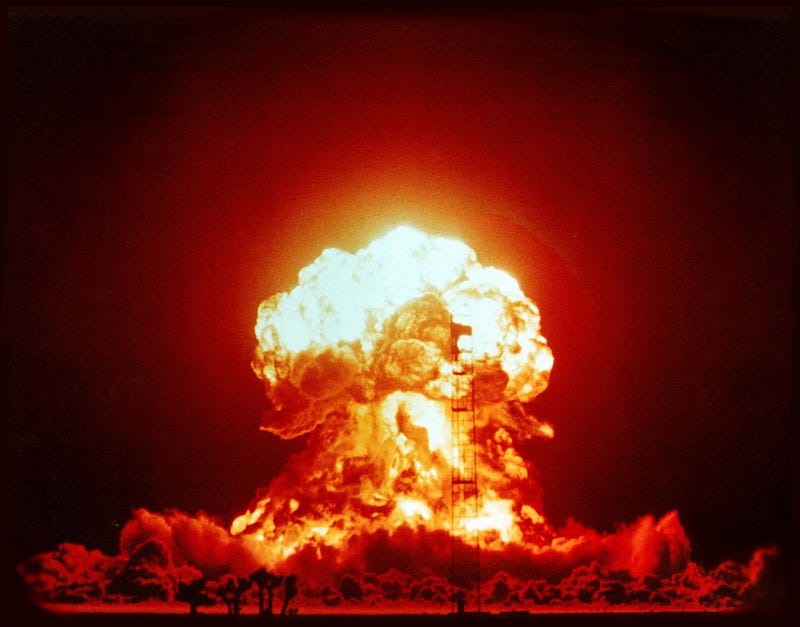

“[Lethal autonomous robots] have been called the third revolution of warfare after gunpowder and nuclear weapons,” says Bonnie Docherty of Harvard Law School. “They would completely alter the way wars are fought in ways we probably can’t even imagine.” And that “killer robots could start an arms race and also obscure who is held responsible for war crimes.”

Militaries around the world are investing in robotics and autonomous weapon systems. There are good reasons for this that range from saving human lives (both soldiers and civilians) to greater efficiency. But what happens when an autonomous system with a goal to improve the efficiency with which it kills, reaches a point where it is no longer controllable?superintelligent Unlike nuclear weapons, the difficulty and cost to acquire weaponized AI once it has been developed will be low and will allow terrorists and other rogue parties to purchase such technology on black markets. These actors won’t show the relative restraint of nation-states. This is a very real problem and we’ll see more news about this well before we get to a world with ASI.

2. Various groups will race to develop the first ASI and use it to gain advantage and control.

Similar to the arms race mentioned above, nations, companies, and others will be competing to develop the first ASI because they know that the first one that is developed has a good chance of suppressing all others and being the only ASI ever to exist. In the opening chapter of his book Life 3.0 Max Tegmark lays out how a company that manages to build an ASI manages to take control over the world. The Tale of the Omega Team is worth the price of the book, in and of itself. It lays out all the advantages the “first mover” to AGI and then ASI gains and all of the rewards that come along with that. It will be hard to convince everyone on Earth to leave that fruit on the tree. This is one of the reasons I believe the move from ANI to AGI/ASI is? inevitable. I hope (maybe naively) that it is some group with good intentions that wins this “last race”.

But these stories need not be relegated to the hypothetical. Russia and China areis racing to develop ever more sophisticated systems as the West tries to create guardrails.

“ Artificial intelligence is the future, not only for Russia but for all humankind. Whoever becomes the leader in this sphere will become the ruler of the world.”

—Vladimir Putin September 2017, in a live video message beamed to 16,000 Russian schools.

3. An ASI itself will turn malicious and seek to destroy us.

Unlike the scenarios above, this requires the AI to “want” to hurt humans of its own volition. Neither I, nor serious AI researchers are concerned with this scenario. AI won’t want to hurt us because they won’t want. They won’t have emotions and they won’t think like us. Anthropomorphizing² machines/programs in this wayare is not useful, and could actually be quite dangerous.

It will be very tempting to look upon these programs — that may indeed mimic human speech, comprehension, and emotions — and believe they are like us, that they feel like us and are motivated as we are. Unless we specifically attempt to create this in them, artificial intelligences will not be made in this image.

4. We don’t align the goals of the ASI with our own.

This is the scenario most AI safety researchers* spend most of their time on. The concept of aligning the goals of artificial intelligences with our own is important for a number of reasons. As we’ve already defined, intelligence is simply the ability to accomplish complex goals. Turns out machines are very good at this. You could say that it is what we built them for. But as machines get more complex, so does the task of goal setting.

* Yes, AI Safety is a thing that organizations like The Future of Life Institute and the Machine Intelligence Research Institute (MIRI) spend a lot of time studying.

One could make a compelling argument (if you’re a biologist) that evolutionary biology really only has one primary goal for all life — to pass on genetic instructions to offspring via reproduction. Stated more crudely, our main goal as humans is to engage in sex and have babies. But as you may have noticed, even though we spend a fair bit of energy on the matter, that isn’t the thing we do all the time. We have developed sub-goals like eating, finding shelter, and socializing that serve to help keep us alive long enough to get to the sexy times. Once we have kids, even though all we have to do is raise them until they, themselves are old enough to procreate, we still find other things with which to occupy ourselves. We go on hikes, surf, take photos, build with LEGOs, walk our dogs, go on trips, read books, and write blog posts — all of which don’t further our goal of passing on our genes.

We even do things to thwart our one job on planet Earth. Some of us use birth control or decide not to have children altogether. This flies in the face of our primary goal. Why do we do things like this? Let’s refer to Max Tegmark’s book Life 3.0 again:

Why do we sometimes choose to rebel against our genes and their replication goal? We rebel because by design, as agents of bounded rationality — we create/seek “rules of thumb”, we’re loyal only to our feelings. Although our brains evolved merely to help copy our genes, our brains couldn’t care less about this goal since we have no feelings related to genes…

In summary, a living organism is an agent of bounded rationality that doesn’t pursue a single goal, but instead follows rules of thumb for what to pursue and avoid. Our human minds perceive these evolved rules of thumb as feelings, which usually (and often without us being aware of it) guide our decision making toward the ultimate goal of replication.

[but] since our feelings implement merely rules of thumb that aren’t appropriate in all situations, human behavior strictly speaking doesn’t have a single well-defined goal at all.¹³

“The real risk with AGI isn’t malice but competence. A superintelligent AI will be extremely good at accomplishing its goals, and if those goals aren’t aligned with ours, we’re in trouble.”

Every post about AI existential risk must mention Swedish philosopher Nick Bostrom’s “paperclip parable”.¹⁴ Sorta like a restatement of the genie or Midas problems, or — restated — be careful what you wish for.

“But, say one day we create a super intelligence and we ask it to make as many paper clips as possible. Maybe we built it to run our paper-clip factory. If we were to think through what it would actually mean to configure the universe in a way that maximizes the number of paper clips that exist, you realize that such an AI would have incentives, instrumental reasons, to harm humans. Maybe it would want to get rid of humans, so we don’t switch it off, because then there would be fewer paper clips. Human bodies consist of a lot of atoms and they can be used to build more paper clips. If you plug into a super-intelligent machine with almost any goal you can imagine, most would be inconsistent with the survival and flourishing of the human civilization.”

— Nick Bostrom, Paperclip Maximizer at LessWrong

So what should we do about this? AI/Human goal alignment is likely to be a recurring theme here at AltText for a while so we will only touch on it now. Life 3.0 puts forth a pretty basic-sounding plan designed to make future AI safe, involving:

- Making AI learn our goals

- Making AI adopt our goals

- Making AI retain our goals

Sounds simple enough but it is actually incredibly difficult to define and carry out a plan like this. And we may only get one shot with it since the first ASI is likely to be the only one to ever be created.

This goal-alignment problem will be the deciding factor of whether we become immortal or extinct when artificial superintelligence becomes a reality.

Other parts in this series:

Part One: An introduction to the opportunities and threats we face as we near the realization of human-level artificial intelligence

Part Two: What do we mean by intelligence, artificial or otherwise?

Part Three: The how, when, and what of AI

Part Four AI and the bright future ahead

Part Six: What should we be doing about AI anyway?

This is such an immense topic that I ended up digressing to explain things in greater detail or to provide additional examples and these bogged the post down. There are still some important things I wanted to share, so I have included those in a separate endnotes post.

Comments